Looking to the future with Alzheimer’s

Subtitle: a guide for patients and families

By Olivia Geen MD, MSc, FRCPC

Geriatrician & Internist

Dear patients and families,

Timing is everything in life. Think of the sequence of events that transpired to bring you to your husband, wife, pet or best friend at the exact right moment when you met for the first time. With big and small events, timing plays a role. Right place, right time.

This article is just like that. I want you to read it only in the right place, at the right time. We are going to talk about some difficult truths, some scary ideas, and some unknowns. You and I, like all humans, do not like difficult, uncertain things.

I have found that the best way to deal with uncertainty, is to get more information, and talk with my friends and family. This keeps us grounded in things we DO know - that we have support, that we are loved, and that we will continue figuring out life together, as we have always done.

So here are the two things you need before going further:

Right place - read this in a comfortable spot (I suggest at home), either by yourself - but with family a phone call away - or with your loved ones.

Right time - this isn't the article to read the moment you've been diagnosed with dementia. This is the article you read a few weeks after - when the initial strong feelings have lessened, even if just a little bit, and you're ready for more information about what the future will look like.

Having said all that, I've had many patients tell me that my explanation of the future is a lot less scary than what they previously thought a diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease meant for them.

So, hand in hand, let's carry on together.

THE FIRST FEW YEARS

You have likely read, or heard, that the journey with dementia is different for everyone. This is true. However, there are some patterns that tend to repeat, and that is what I will describe here, with different scenarios clearly mapped out. Knowledge is power, and when it comes to your life, power gives you control, dignity, and independence.

This section is for those who have been diagnosed early in the disease - meaning your symptoms started in the last few years, and have only affected a few areas of thinking - you’re more forgetful and perhaps have more trouble with getting your words out.

First, let me briefly outline what early Alzhiemer’s disease looks like and how it is diagnosed, in which I hope you recognize your own experience. If you don’t, you might want to revisit the diagnosis with your doctor - it may still be dementia, but a different type of dementia. Alzheimer’s is the most common type of dementia (60-70%), but there are others like Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Frontotemporal, Vascular, Primary Progressive Aphasia, etc.

What does Alzheimer’s Disease

look like?

This is an overview of what getting Alzheimer’s disease might have looked like for you and your family. The first signs likely were:

Forgetfulness - all people with Alzheimer’s disease become more repetitive in their storytelling or questions to friends or family. Initially you were forgetful over a few days, but later on, you became (or will become) forgetful within a few minutes. Your memory of events that happened long ago is pristine. You know everything from your childhood! But the things that happened yesterday? Not so much. Alzheimer’s affects your “short-term memory”, and only much, much, later in the disease will you forget “long-term memories”.

This can also look like misplacing items around the house, forgetting parts of conversations, or misremembering recent events. Eventually you find yourself forgetting to take your pills, forgetting to pay bills, and/or getting lost while driving. You might also forget that you forget - and get angry when someone points out that you’ve asked that question already.

Communication - some people with Alzheimer’s have trouble coming up with the words that they need. We call this “word-finding difficulty”. You’ll be mid-sentence, and suddenly the word you need next just doesn’t come to mind. You’ll search… stall… realize it’s not coming… get a bit panicked and either talk around the thing (“you know, the thing with the handle on top… you put water in it” - “Kettle!” juts in your daughter, trying to be helpful), or you simply change the topic (“oh, it doesn’t really matter, I don’t worry too much about those things”).

This might also look like becoming more quiet, not offering as much in conversation, and trouble following along with longer sentences. You might give up your crossword puzzles, read less, and not want to attend social events because the speed of conversation makes you feel left out, and you might even be afraid people will notice - you don’t want anyone to worry or think you’re not alright.

Irritability - some people with Alzheimer’s can start to have more anxiety and irritation - that uneasy feeling inside that something isn’t quite right. You’re starting to sense that your mind is feeling a bit more "fuzzy" than it used to be; you’re noticing that things can make you feel overwhelmed and frustrated easily. This might look like becoming quick to snap at your spouse, feeling easily irritated, and finding it hard to cool down once you feel that surge of anger.

You might be responding this way because the parts of your brain that control impulses are getting fuzzy, along with the memory centers.

However, it might also simply be that deep down, underneath the annoyance and irritability, is fear. You’re afraid not only of what’s happening to your memory, but also afraid that people will notice and think you can’t take care of yourself anymore - that they will take away your independence. Fear is normal. All adults, regardless of having dementia or not, fear losing our independence - we value our capabilities and hate being told what to do. I’ll come back to this point later in the article, and show you how you can ensure you keep your independence, no matter what happens, throughout your disease.

For your family - this is one of the symptoms that you have enormous power to help with. You don’t need to correct your loved one on every little thing. Let 90% of it go. Don’t ask them - “don’t you remember? We talked about this yesterday”. They don’t remember, and you repeating it out loud can feel irritating and perhaps even insulting to their sense of self and pride. Love them as they are, and let the little things go. Even more, don’t try to quiz them in the hopes of maintaining their memory. Yes, keeping the mind active is helpful (as we’ll get to below), but when you incessantly quiz someone who doesn’t want to be quizzed, you’re going to lead to more rifts in your relationship, which is much more important than knowing what happened yesterday. I know it’s hard, and you might feel compelled to correct them because deep down, you’re scared too. That urge to remind is coming from the hope that maybe this time they’ll remember, and this will all have been a dream. You’re not alone in that, and you deserve grace in all of this too - the diagnosis affects you too. Just know that by letting most of the memory slips go, you’ll both be happier in the end.

How is Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosed?

Your doctor will ask questions to find out what signs and symptoms you’re having (above), and check these other things:

Daily activities - doctors will diagnose dementia (rather than pre-dementia or normal aging) when your symptoms are significant enough to cause important areas of your life to slip, unless someone else steps in. Specifically, we ask about daily tasks like remembering to take your medications, pay your bills, cook meals, keep house, and drive safely.

Memory test - you have probably had a "memory test" done, called the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Standardized Mini-Mental Status Exam (sMMSE), or Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) if english is not your first language. It should have been done when you were relatively well (not more confused than on a normal day in the last 2 weeks) in a quiet space with your glasses and/or hearing aids in.

The score you got is unique to you. As a specialist in dementia, I don’t really worry about the number on its own - I care about what symptoms you’re having, and combine that with the score I would expect you to get if you were well, based on your personal history and education level. I’ve had many patients who grew up in a non-english speaking country, were given education only to grade 3, never wrote tests, and worked in the home when they came to Canada. A score of 12/30 on the MoCA could be entirely normal for them. It has nothing to do with intelligence, and more to do with how your mind has been trained to think. This means that your doctor should compare your score to what someone similar to you should get if they were well.

On the other hand, if you were born in an english speaking country, went to university, and worked in a highly cognitive job - like a lawyer, professor, doctor, etc - you are a top-notch test writer. When at your peak self, you would probably score 40/30 if it were possible. This means that when you score 26/30 in my office, I’m worried. While this score is technically "normal" on the cut-off scores you might read about, for you, it tells me there’s been an abnormal decline.

Physical Exam - your doctor should examine you for signs of neurologic changes in the body - testing your strength, your nerves, your balance, coordination, and stiffness. In Alzheimer’s disease this exam should be normal, until you’re in more advanced stages. If you have changes, it might mean you have a different type of dementia, or that you have a mix of a Alzheimer’s and something else (such as a mix with vascular dementia from previous strokes, alcohol-related dementia, etc).

Blood work and a CT or MRI scan of your brain - this helps us make sure there isn’t something else causing your symptoms, rather than it all coming from Alzheimer’s disease. We don’t often find something truly “reversible”, but sometimes we find something that’s a bit off, and by fixing it, we might get you a bit better for a while. I’ll list the tests so you know, but won’t go into the medical specifics beyond that: CBC (looking at Hb), calcium, TSH, B12, sodium, potassium, creatinine, and HbA1C. If you have symptoms not consistent with Alzheimer’s disease, you might get other tests like HIV, syphilis, lumbar puncture, etc. Not everyone needs them if the story and testing look like Alzheimer’s disease.

On your CT or MRI scan we’re looking for strokes, chronic build up (similar to the chronic build up that can happen in the arteries of your heart over time), tumors, or parts of the brain that have shrunken (atrophied) more than others.

For Alzheimer’s disease, your scan will be pretty much normal in the early stages. Over time, we’ll see shrinking in your hippocampus (the memory centers of the brain), before the rest of your brain starts to shrink too.

This means that you can have lots of symptoms, and a CT scan can get reported as “normal”. The changes are happening at the microscopic level, but are still there. Don’t be alarmed by a normal scan.

Now that we’ve covered the basics of what early Alzheimer’s disease looks like, and how it’s diagnosed, let’s talk about what you can do to help in those first few years.

What can I do to help my brain?

Safety First

The things you must do in the early stages - either with private-paid help or the help of family and friends - is find safe ways to manage your medications, finances, and likely stop driving.

If you don’t you are at risk of harming yourself by overdosing on your medications (or forgetting to take them and having worsening of your other health issues), falling prey to financial scams from strangers or even people you know, and seriously hurting yourself or others while driving.

The driving is a point of contention - I won’t go into it more now since we have a lot of other things to cover - but know that it doesn’t matter if you’ve never had an accident before. The changes in your brain are increasing your risk for accidents in the future, every time you get into the car.

Think of it like driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The person who just had 3 drinks might have never had an accident in their life - but their mind isn’t in its normal state. Drinking drastically increases their risk of hitting and killing someone else. Don’t let that be your legacy. Stop driving when your physician tells you it’s time.

How to slow down the disease

There are two ways to slow down the disease - natural lifestyle changes, and with medications.

Lifestyle Changes

(click on the links below for more information on each topic)

Before dementia:

We know that when we are normal / have pre-dementia (termed “mild cognitive impairment”) there are a number of things we can do to make our situation better. These include: walking, following a mediterranean diet, wearing hearing aids if you need them, getting tested for and treating sleep apnea, managing high blood pressure, reducing excessive alcohol intake, and keeping your mind active.

With dementia:

Once the disease is full-blown dementia, only a few of these changes have been shown to make any real difference. These include getting tested for and treating sleep apnea, and doing things that keep your mind active.

I would also add ensuring good sleep (with or without sleep apnea), as there is more and more evidence that sleep is tied to how well your brain works during the day, and exercise, because there are other benefits (like socialization, if exercising in a group) that could be missed in a clinical trial.

Other general health advice, like reducing alcohol, managing high blood pressure, and getting your hearing checked and treated may not change your disease, but will still help your overall health and vitality.

Dementia Medications

There are no medications that cure dementia. Even slowing down the disease is hard. The USA has new medications for pre-dementia or early disease, but as a Canadian physician, I won’t comment on it further here.

Our best drug in Canada is Donepezil (Aricept). You can read about the evidence for the drug here, and I like this study in particular as it was done over a longer period of time.

Here’s what can happen when you take the drug:

Get better: 1 out of every 6 people that take the drug every day get better for a year or so - however over time they will still continue to get worse and eventually die from the disease.

Does nothing or slows it down: in the remaining 5 out of 6 people who take the drug and don’t see an improvement, it is possible that the drug is either doing nothing for you, or slowing down the disease. We can’t know which one will happen for you, because the natural speed of change of the disease is different for everyone. We don’t know what it does for you in particular.

You might be someone who would have gotten worse quickly, and now you’re getting worse more slowly.

Or, you might be someone who would get worse slowly, and on the drug you’re still getting worse slowly, so the medication isn’t really doing anything for you.

Trade-offs: all drugs come with trade-offs (i.e. risks and side effects). For this reason, if you start the medication and don’t see a clear improvement and you get intolerable side effects, don’t feel like you’re missing out by stopping. You might not have been benefiting anyways.

There are also some reasons why you might not be eligible to take the medication, because of issues with your heart, history of seizures, asthma, etc. Make sure you discuss with your doctor to make sure it is safe for you.

How to manage the symptoms of the disease

There are lots of things you can do to reduce the impact that your symptoms have on your day-to-day life in early disease.

How to manage forgetfulness

Make routines

In Alzheimer's Disease your short-term memories (recent events) are affected first. Long-term memories (like places, people, routines) aren't affected for a long time.

What you want to do, as soon as possible, is make memories that go into the long-term storage part of your brain. This means learning repetitive routines.

For example: put things in the same place every time in the kitchen, bedroom, and bathroom. This should ideally be done as soon as possible (we should all start in our 20's!), so you have a better chance of remembering this routine for many years into the disease. Over time, as the disease affects more of your brain, you won't be able to learn new routines, and you will eventually forget many routines that you have, but for right now - build what you can.

Make a schedule

You might also consider doing the same activities on the same day each week; Sunday is coffee with friends; Tuesday is swimming; Friday is movie night with your spouse; Monday and Thursday are long-shower days (get yourself pristine).

This will add structure that becomes a long-term memory. It is very common for patients in middle stages of the disease to need reminders to shower, and you might even get resistant to doing this part of a daily life routine. This can make it really hard for your family to help you stay clean. If you can start to set routines in your mind for days of the week that are “shower days”, this might be a way for your family to help you later in the disease.

Write things down

Making lists and writing down important things can help you keep things organized. Buy a journal where you can write down things about family, friends, health, house, etc.

This could also mean getting a calendar or date book.

Use technology

If you like technology, you can get a digital assistant like Alexa (from Amazon) to help you keep track of things. Ask her to remind you to take your medications, remind you of upcoming appointments, and other things.

You can also get digital medication systems that ring when it’s time to take your pills.

Use these tricks to boost your memory

Meeting someone new? Associate their name with something else you enjoy. For example, I’m Olivia - I like olives.

You can also boost memory through sound - say what you’re doing out-loud. “I’m putting the keys down on the tray at the front door”. You don’t want too much sound though - keep background noise to a minimum when you’re trying to focus. Turn off the TV, music, etc so you can focus just on the task at hand.

How to improve your communication

Stay social

I know it’s hard when you can’t follow along with the conversation, or find it hard to pull out the words that you need to explain. However, keeping your mind engaged, and being in the presence of other people, is incredibly helpful for the brain.

You don’t need to be center stage - you can attend the family gathering and sit and enjoy the presence of others, without needing to pipe in.

You can also ask your friends and family to reminisce with you about old times - these memories are solid and the words often come more easily.

Get your hearing checked

The last thing you want is to miss out on an easy opportunity to boost your connection with the world around you. Get your hearing checked and wear your hearing aids every single day.

Even if no one is around, having the background noise of the fridge, the creak of the floor boards, the chirp of a bird, are all things that keep your brain engaged.

How to improve irritability

Open up to people you trust

Brene Brown is one of my favourite authors and researchers. She teaches how being vulnerable - the ability to lean in to uncomfortable situations instead of shutting down and keeping things locked inside - is our greatest super power for connection and happiness.

When feeling afraid, instead of blocking that feeling and turning it into frustration, take a deep breath, and lean in. When your daughter tells you you’ve already told her that story, say "Hearing you say I've already told you this story makes me afraid".

This is your opportunity to ask for help, in the way that makes sense to you. Maybe this means saying "don't tell me I'm repeating, unless I'm going on about it for a really long time", or "just promise me you'll help me live at home until the very end".

Dementia is a disease that more than any other point in our life, requires us to let other people in.

Ask your doctor about medications

In some special circumstances, your irritability and angry outbursts might be severe enough to warrant taking a new pill. This could be an antidepressant or something called an antipsychotic. Make sure you ask lots of questions of your doctor if they suggest this for you. It’s not wrong to take them, but you also don’t want to become over medicated unless it’s truly necessary for you.

The Bottom Line

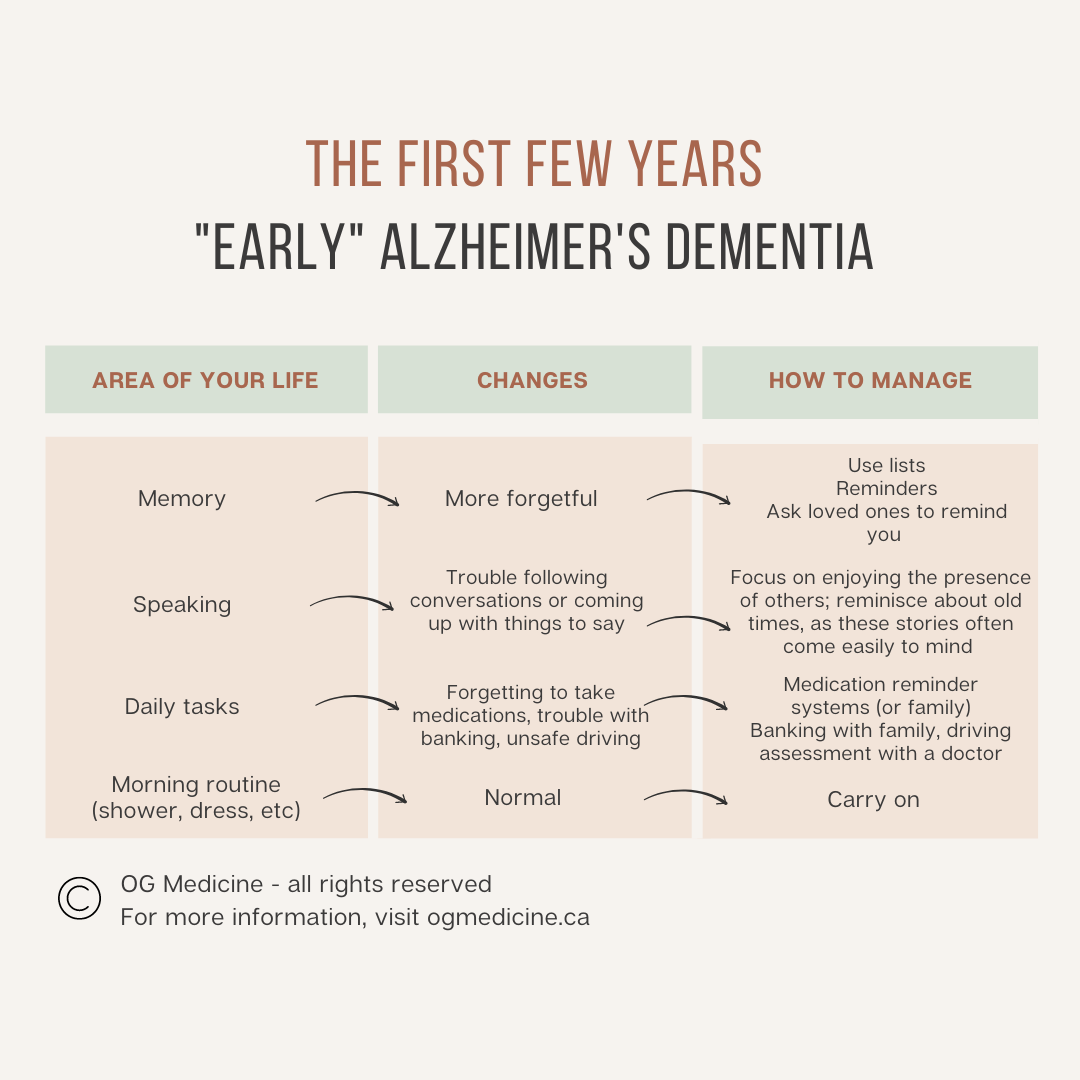

In summary, in early Alzheimer’s disease you will notice changes to your memory, speaking, and/or more irritability. These changes are large enough to impact your day-to-day life with managing medications, finances, and/or driving.

This means that you are going to need help with those important day-to-day things, make some lifestyle changes to slow down the disease, consider taking a memory pill, and learn new tricks for improving your memory, communication, and mood.

We also need to remind our family and friends not to treat us like a child, because you aren't one. You've lived a life and gathered wisdom and are an independent adult. Build routines, ask for help, and maintain a balance between independence and letting people in.

Homework for the early stage

I used to be an educator at McMaster University, so any teaching/advice from me is incomplete without a bit of homework.

In the early stages, these are the things you need to get set-up, so that things go according to your plan in the later stages (which we will get into next).

1. Legal stuff - set up a power of attorney, living will, and other legal documents so everyone knows who you want to speak on your behalf (down the road) and what decisions you want them to make for you. Check here if you’re Canadian, and here if you’re American, but a quick google will also get you started in whatever country you’re from.

2. Home safety - make sure you have someone checking in on your medications, finances, driving, and kitchen safety. Leaving pots on the stove is a warning sign that the stove should be unplugged (and usually means you get upgraded to family dinners or a community food delivery program). For more home safety tips visit this site.

INTERMISSION: HOW LONG WILL I STAY IN THE "EARLY" STAGE?

It's hard to say how long you will stay in the early stages, before moving on to the "moderate" stage (which we discuss after this intermission). To answer this question, I need to talk to you about something called “prognosis”, which means estimating how long you have until things start to change.

This is a difficult topic, and because of the sensitive nature, I’ve actually put the information in a different article that you can read by clicking here. If you don't feel ready right now for a timeline, I didn’t want you to have to scroll past it.

I will still talk about some of these things when we get to the last section, which is on "final" or "end-stage" dementia.

…

THE MIDDLE YEARS

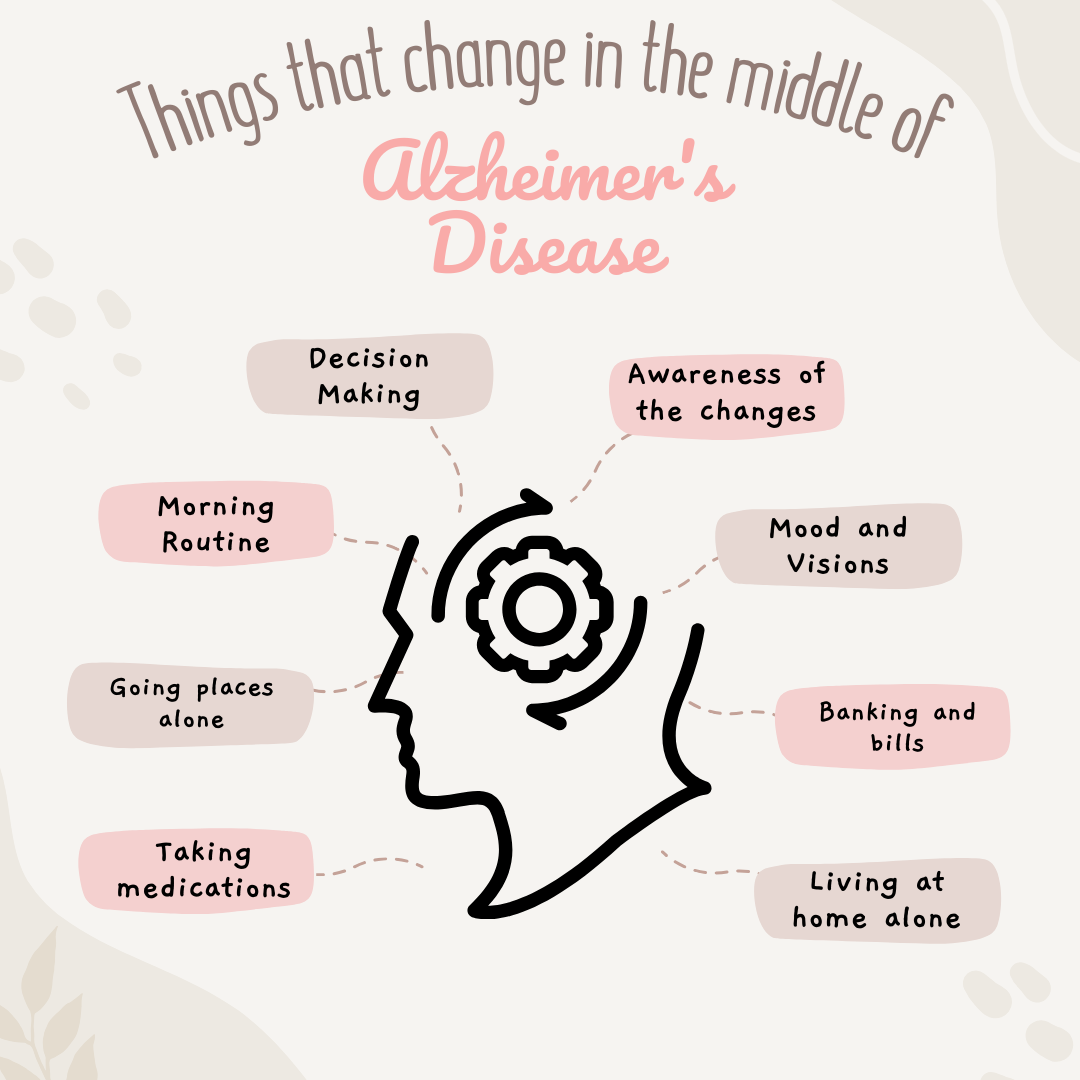

This stage is marked by the need for help with most of your daily activities - like cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry, in addition to medications, finances, and driving.

If you live alone, someone is likely checking in on you every day either in person or calling over the phone, and someone has taken over managing your medications and finances.

Your memory is getting worse, and you are more repetitive now, possibly even within the same conversation. You still know who your family and loved ones are, and you still remember lots of details about your life, but you aren't making many new memories.

The amount of help that you need increases gradually over time. For example you might go from cooking meals, to forgetting to include certain ingredients, to making simple meals like eggs and toast, to making a pot of coffee, to not being able to use the kettle or microwave.

However, as I wrote before, your brain isn't changing in all areas at the same time, although there is a reasonably predictable pattern.

For Alzheimer's, this pattern goes:

Memory

Communication

“Executive” decisions, like judgement, planning, multi-tasking, etc

Behaviour - this can range from early irritability, to depression, to hallucinations and even delusions.

Difficulty using familiar things (like the microwave, TV remote, or laundry machine)

Finding your way around in familiar places.

Some of these symptoms might pop up slightly out of order from this, but in general, this is the pattern that you can expect to see.

However, you can still do a lot of things during these gradual changes, and in fact you might become better at other things - there are stories of people who have become beautiful artists as their inhibitions were removed by the disease. Having dementia doesn't mean you can't still have fun, enjoy new experiences, and have meaningful moments with others.

What I want is to give you a balanced idea of what you can expect. With that in mind, here are the list of things I talk to patients about in the middle stages.

(Note: I’m writing this for you as you are now; when you are in the middle stages of dementia, understanding this information and the significance of what I’m saying will be difficult if not impossible at that stage. We call this “lack of insight”. Your friends and family will also benefit from reading this part and being heavily involved in this stage).

Making healthcare decisions

Depending on how complicated the decision is, you might need help from your Power of Attorney (POA) to make a decision. You can still be involved in the process, and your POA should make the choice that they think you would have made, if you could manage without them.

This could be something like deciding whether to go for an elective (meaning not life-saving) surgery - if you aren't able to remember all the information the surgeons tell you (memory), and consider risks and benefits (judgement), and communicate your choice (language), then the doctors will have to ask your POA what you want them to do.

The most important thing is to have told your POA and put it in writing (advance directives) so they don't have to scratch their heads about what you would have wanted. This should have been done in the early stages of the disease (see your first homework assignment above).

Making financial decisions

Similar to healthcare, managing complicated finances - like investments, taxes, and big purchases - need to be supervised and perhaps even taken over entirely by your POA for finances.

It is imperative that you have selected someone that you trust for this role. They will have access to your money, which you will need to keep safe for paying for private supports later in your disease (and/or leaving to your family, charities, etc, when you’re gone)

Awareness of your disease

As I mentioned above, you will have decreasing awareness of how impaired your memory and thinking have become.

In some ways, this reduces your suffering, but can make it more challenging for your family. They will have to be more creative in their strategies for caring for you, because you may not think that you need their help.

A common story I hear (and mentioned earlier), is not remembering that you haven't showered in a few days. Family will be at their wits end trying to convince you to take a quick bath, while you are quite adamant that you showered yesterday.

Your family will need to learn new strategies for helping you at this stage, and resources are available for your family. Sometimes they will just have to pick their battles, so to speak. It’s okay to not have a bath every day (or even every week).

Your loss of awareness does not extend to other parts of life - you still feel enjoyment, laughter, and the emotions of love and connection that you have with your caregivers and loved ones. You live life mostly in the present.

Getting lost

Some people start to get lost when they leave the house, because they can't remember how to get home. Alternatively, you might no longer remember that you live in this current home - and instead be insistent that you “go home” to where you lived 10, 20 or even 30 years earlier.

This means you could be getting turned around even in “familiar” places, because you no longer have access to the memories that make them familiar to you.

You will absolutely need to stop driving at this point (if you have not already).

As well, if you keep trying to leave the house without someone with you (what doctors might call “wandering”), your family may need to take additional steps to keep you safe (check this website for resources).

Mood swings and visions

For 80% of people with Alzheimer's Disease, they will have changes to their mood, social awareness (i.e. become disinhibited), and/or have visions (i.e. hallucinations) or incorrect beliefs (i.e. delusions).

Hallucinations tend to be vague - seeing people outside the window that aren’t there; seeing people in the house; sometimes hearing voices.

Delusions are fixed ideas about things that aren't true, like becoming convinced people are stealing from you, tampering with your food, or coming to harm you.

Sometimes you might yell or seem enraged because of these changes. This doesn't happen for all people, although you will likely get some version of these events. The medical term for this is "Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia", or BPSD for short.

There are medications that can stop or reduce these symptoms, such as antidepressants (for mood swings), and antipsychotics (for hallucinations and delusions).

Importantly, even without medications, these symptoms do not last forever. Eventually, like a passing wave, these strange behaviours will go away over several months or a few years.

Bathing and dressing

At some point in the middle stages, you will need help with your morning routine. This might look like figuring out what clothes to wear for the season, or getting the clothes on properly (is it an arm hole or the neck hole?). When it comes to showering, you might need reminders for what to use when - shampoo, soap, conditioner.

You are still able to do part of the job on your own, and I always encourage families to not do too much, unless they have to, if you are someone who always highly valued your independence.

If you are resistant (as discussed above), this video by dementia educator Teepa Snow, is excellent for your family.

Safety at home

Living at home can become impossible in this stage unless you have someone that lives there with you, or enough external people can be coming into the home throughout the day to help - personal support workers (PSWs).

The essential parts to staying at home are:

Medication management - someone needs to give you medications if you forget on your own (and don’t take them even when a reminder is given by family calling or Alexa (the digital assistant I mentioned earlier)).

Meals - the kitchen can become dangerous at this stage because you forget to turn off the stove. Or you may simply no longer know how to make meals on your own. This means disconnecting the stove, or making sure someone is at home with you all the time if you’re still trying to use the stove.

Family will need to prepare meals for you, or have meals delivered to your door, or you will need to move in somewhere that can provide meals for you - a retirement home or long term care.

Stairs - your coordination can change in middle-to-late stages of the disease and you can be at high risk for falling up or down the stairs.

Wandering - see above section on getting lost.

Aggressive outbursts - these can put you or your loved ones in danger - see below.

At some point, if these safety concerns cannot be managed at home with a combination of family support, private caregivers, and government funded personal support workers, a doctor will suggest that you move into either a retirement home that has memory care supports, or into long-term care.

Ways to try and remain at home:

Have enough friends / family to be able to have someone present with you in the house all day and all night long

Have enough money to pay someone to do the above

Use the government / private insurance resources for personal support workers (in Canada, this is quite limited, in the range of 1-2 hours a day)

Attend adult day programs - that are designed for people living with dementia, where there are trained workers to look after you while your family/friends go to work or take care of other matters in their own lives.

The decision between retirement home and long term care will come down to how severe your symptoms are, and how much you can afford to pay (unfortunately). There are some retirement homes that can provide 24/7 supervision and have nurses and doctors available all the time, but they can be extremely expensive.

Bottom Line

The middle phase of Alzheimer's dementia is marked by a lot of changes in how you think and therefore how you behave and take care of yourself.

It can feel like things are changing very quickly, and families often tell me “they’ve changed more in the last 6 months than in the last 4 years”. That is a sign you are in the middle stage.

It's a time where you are going to need more help from friends, family, and personal support workers. You might need to go to day programs, move in with your children if you live alone, or move to a retirement home or long-term care.

THE LAST FEW YEARS

The last few years are the ones that most people worry about when they think of getting dementia. Following my promise to be honest and transparent, I acknowledge there are very difficult moments in this stage.

However, there are also ways that you can be in control over your life in the end.

These are things that I call "natural off-ramps", built into the fabric of your life. These are different from more recent pathways legalized in Canada, such as Medical Assistance in Dying.

Check in: More tea? Stretch those legs again. Maybe check your phone for messages. Okay, all together now - "Knowledge is power!". Let’s jump in together.

Here’s what to expect in the final years of Alzheimer’s disease:

Loss of Awareness

You have very little to no awareness of your difficulties in this stage of the disease. You will still have plenty of feelings about people and events around you - love, loneliness, fear, joy, anxiety, sadness, happiness, contentment, etc - but you won’t understand that the changes around you or how people are treating you are coming from how much help you need.

On the other hand, you live almost entirely in the present now. You aren't concerned about the future, and you have forgotten much of your past. You may not recognize your spouse or your children, other than a deep, unshakable knowing that these are people you love and trust. The feelings remain, but the specifics of who they are drift away like shifting sands.

Due to your lack of insight, you do not suffer from your loss of memory and thinking. The end stages are more emotionally difficult for your friends and family.

Physical Dependence

In the final years, you need help with all of your morning routine. Bathing, dressing, and toileting become a team sport. At some point you become incontinent of bowels and bladder, and your family will need to purchase incontinence products for you to wear.

If this degree of physical help cannot be managed in your own home, you will need to move to retirement home or long-term care, where there is more support to help with these activities.

Worsening with Hospitalizations

At this stage, our minds have reverted to our younger years - the way you communicate, move, and behave may seem similar to that of a young child - and our needs are much the same.

Love, comfort, safety, and kindness are what we need now, rather than being poked and prodded for blood tests, overloaded with medications, or going through surgery.

Any interaction with the healthcare system will be confusing, often distressing, and often times require sedating medications or even physical restraints to allow the medical team to administer treatments.

As much as possible, try to get any care that you need in your home, retirement home or long term care facility.

Difficulty Eating

As the Alzheimer’s disease spreads throughout the brain, your ability to coordinate the muscles needed to swallow no longer get the proper signals from the brain. You will start to choke on food that isn’t the proper size and texture for you.

A speech language pathologist may do an assessment to determine what kind of food you can safely eat - minced diet, thickened liquids, etc.

At some point, you no longer understand how to use utensils. Your family or someone else will need to feed you. Finger foods are also a good solution in these situations (if you are still eating solid foods).

Choking on food and swallowing food into your lungs, rather than into your stomach, become common occurrences. Most people with dementia die from recurrent pneumonias that are related to food in the lungs, called “aspiration pneumonia”. You can read more in the article on timelines in Alzheimer’s.

Feeding tubes are not recommended at this stage by all leading dementia advocacy organizations, such as the Alzheimer’s Association. The reason is that you can continue to aspirate, since food that is injected into your stomach through the feeding tube can still flow up your esophagus and down into your lungs. What’s more, because you don’t know what this tube sticking out of you is, you tend to pull on it and often end up pulling it out. This means going to the hospital to have it reinserted. These trips are highly stressful on your body and mind. To prevent you from pulling it out, your family would need to restrain you to the bed. As a specialist, I do not recommend feeding tubes for any of my patients.

Difficulty Speaking

In the last year or so of life you will no longer remember how to speak, nor even what words are. Your mind is like a newborn. You will enjoy hearing the calming and comforting voices of your family and friends, but you won’t engage or know what they mean.

Difficulty Moving

In the last year or so of life, your brain no longer communicates with your body on how to walk. Even with the help of a walker, you can’t get your legs to move and support you. You will need a wheel-chair, and someone else to push you.

Eventually, you are not able to coordinate the muscles in your torso that hold your body upright. As a result you’ll spend all of your time in bed. To move in and out of bed you will need to be lifted in and out using a lift. You will not stand to shower, but be bathed in bed or in special tubs that can accommodate your needs.

Frequent infections

In the last few months of life, you will go through a serious of recurrent infections. Your body is getting weaker and frailer, and it gets sick more often.

You will have frequent fevers and be put on antibiotics often to kill whatever bug is making you sick. Sometimes when the infection is in your lungs and severe, you may need oxygen and intravenous antibiotics and fluids to stay alive. This will typically require you to go to hospital, unless it can be provided where you are.

Eventually however, even this will not be enough.

This brings us to the last section - the end.

The End

The following information will give you control over all phases of your journey, even at the end. You will figure out what your limit is, when your family will know that you've crossed it, and what to do about it when the time comes.

I wish that dementia didn’t unfold the way I have described, or that we had drugs to cure it. Hopefully within the next 10-20 years we will. However, even if we found cures, the honest truth is that we must all die someday. Birth and death are the only two guaranteed experiences of being human.

There are three ways that people (with or without dementia) die - either when your brain, heart, or lungs completely stop working. Without these vital organs, anyone will die.

In dementia, it’s typically a mix of brain and lungs, with the majority of patients dying from severe pneumonias that are a consequence of the brain no longer working properly.

However, as I mentioned earlier, these life threatening events can be understood as naturally occurring “off-ramps”. Depending on your values around life and views on what an acceptable quality of life is, they are gifts from your body - giving you a natural way out.

You don’t necessarily need Medical Assistance in Dying (although it is an option in Canada, and a larger topic for a different article), and you certainly do not need to commit suicide, which is an extremely sad off-ramp that some people newly diagnosed with dementia take, to avoid even the possibility of the end stages I’ve described.

I’m here to tell you, don’t do it.

You do not need to take your own life. Your life will end naturally, if we let it. You simply need to tell your family at what point you want them to let you go.

To do that, let’s look at what I call the “Map of the End”.

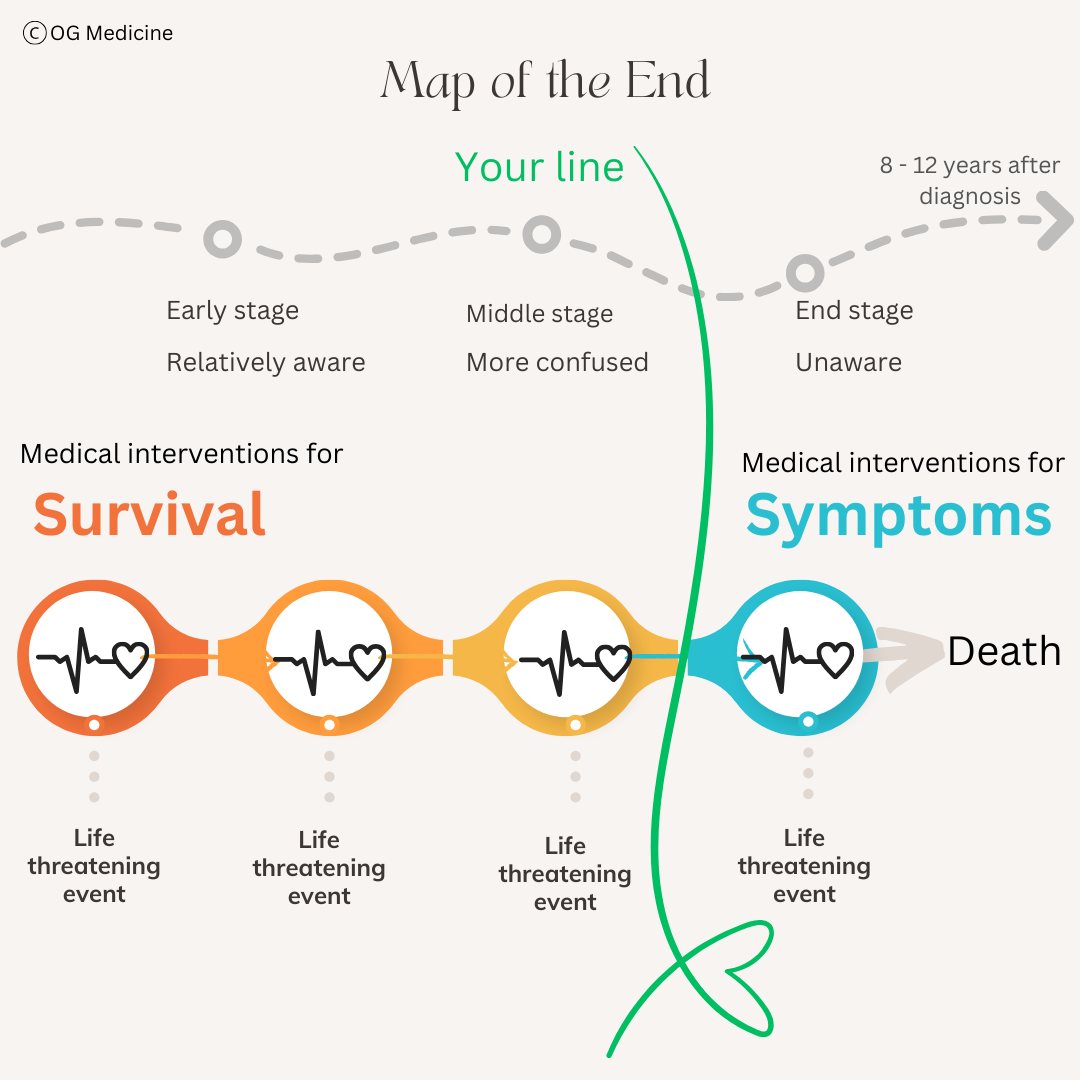

THE MAP TO CONTROL YOUR FUTURE

This is the stuff that no one writes down, but doctors in the hospital will try to communicate to your family and/or POA in moments of crisis. It is much better if you can study the map in advance, and tell your family where your line is.

At the top of the image, we have your path through dementia, in the absence of any curative treatments (i.e. the world we live in right now, unfortunately). From the time of diagnosis, you have on average 8-12 years remaining, with a maximum of around 20 years in very rare cases (see the prognosis article here for more details).

You’ll notice I’ve simplified the map by just stating how aware you are of what’s going on during each stage of dementia. Refer back to the other sections in this article to remind yourself of what each stage entails.

The green line is personal to you - you can put it anywhere on your timeline that you choose. It is the line between medical interventions with the goal of survival, and medical interventions with the goal of symptom control.

The choice is yours. It’s as simple as that.

You can decide for yourself at what point you think your day-to-day life would be more suffering than joy, based on your values and personal beliefs, with no expected improvement, only worsening. Once you’ve passed that point, your POA can tell the doctors to continue to do everything in their power to keep you comfortable - no pain, no difficulty breathing, no anxiety, no distress, and they will not do anything to hasten your death. However, when something life-threatening naturally comes up, it will be allowed to run its course, keeping your comfortable all the while.

I’ve had patients with life-threatening infections who survived without any interventions for survival. The natural course for them was for their body to fight the infection on their own.

I’ve also had patients in the same circumstances, who passed away within a few days to weeks comfortably in their sleep. The natural course for them was for their body to slowly, gently, shut down.

The subtext here, is that we have the power in medicine to keep people alive past when they would have otherwise died. This is desirable during most of our life - humans throughout history have sought medicinal attention when they are unwell - from doctors, healers, shamans, etc.

However, western medicine can now keep you alive even when your values and views on an acceptable quality of life are being crossed. You need to tell us to let your body decide.

Again, this is not Medical Assistance in Dying (a larger conversation for another article). This is allowing natural death, while treating any uncomfortable symptoms that might arise.

Knowing this, you can take control of what you do or do not experience during your years with Alzheimer’s Disease.

HOMEWORK - A FEW WEEKS FROM NOW

A few weeks or months from now, I want you to sit down, and think about what you love most about living. I want you to think about what makes you want to keep going every day. Write that down. Then I want you to think about what makes you who you are. What are your values, what is important to you? Write that down. Now I want you to think about what scares you most about dementia. What you are afraid of losing in the end. Write that down.

Now sit back, and look at what you've written. What jumps out at you? Do you see themes? How could you take what you have written, and put it into a sentence that tells your family what the goal is for your care in the end. How can you use these words to draw a line in the sand (the green line on the map), that clearly tells your family what will be acceptable, what will not be, and how they will know when you've crossed it and are ready for the end.

Some examples might be:

Home

Goal: to live at home until the end.

The line: If I need to move to a long-term care home, I want you to treat my symptoms, but do not do anything that stops my natural death.

Family

Goal: to show love to my family until the end.

The line: If I no longer recognize who you are - that you are my husband/wife, son/daughter - then I want you to treat my symptoms, but do not do anything that stops my natural death.

Independence

Goal: to maintain my independence until the end

The line: if I can't feed myself, dress myself, bath myself, or go to the toilet on my own, I want to start preparing for the end. I want you to treat my symptoms, but do not do anything that stops my natural death.

You’ll notice that with each of these scenarios, it doesn’t necessarily matter how much you remember, how quickly you forget information, whether you still enjoy your favourite TV shows, etc. What matters is what is important to you - the goal that you have laid out clearly, and the line in the sand.

Sometimes distilling the message down to the things that matter most can ensure that you remain in control, until the very end.

After doing your homework:

Put your goal and line in your advance directives/ living will.

Have a conversation with your family. Have them read this article first, if they haven't already. Tell them what matters most to you, and how they can help you take control of the disease and make decisions that make sense for you, right up until the very end.

FINAL REMARKS

You did it. You made it through. I am so proud of you. You are now armed with the information you need to make choices that suit you - that keep you safe, comfortable, and in control until the end.

I hope you can now see that there is no one "right" way of dealing with dementia. There is only your way. You get to be the master of your own fate.

Your friends and family are there to support you, as are your doctors, nurses, personal support workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dieticians, speech language pathologists, and the list could go on. We are here, rooting for you, caring for you, helping you in any way that we can.

As we come to the end of this article, I want to thank you for being brave with me. It is hard, as a doctor, to say these things. As a specialist in dementia, I have these conversations with patients and their families every day - and it never gets easier.

Every time I explain, I feel the weight of my words, and I wish that I could follow it with - and we have a cure.

Until then, I cannot change the end of your disease, but I can change your experience of the journey through it, and help protect you from losing who you are, even as your memories fade.

I hope that this article brings you confidence for the road ahead.

Yours,

Dr. Olivia Geen

Division of Geriatric Medicine

Dr. Olivia Geen is an internist and geriatrician in Canada, working in a tertiary hospital serving over one million people. She also holds a masters in Translational Health Sciences from the University of Oxford and is widely published in over 10 academic journals.