Negotiating contracts with startups

Subtitle: My experience on contract negotiations

By Olivia Geen, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Upfront, let me say that the following is based on my experience. It is not legal advice, and I am not a lawyer. I am a physician who works as an advisor to healthcare startups and have experience negotiating contracts.

If you are considering entering into a contract position with a healthcare startup, it’s important to consider the risks and benefits and ensure the contract protects you as much as it protects the startup.

Talk to people. Ask advice. Consider getting a lawyer to look it over. If you know people in the startup space - even if in a different industry than healthcare - reach out and ask for 15 minutes to chat.

I was fortunate enough to have a friend working at MedStack (the company that helps digital healthcare startups manage their HIPPA compliance), and he was able to look at my first contract and give me advice. This was invaluable. Shout-out to my friends.

This article is therefore intended to give you a scaffold of what to think about when signing on to a cool startup. You’ll need to do your own due diligence to round out your contract experience.

It might seem scary at first, but working with a startup can be an incredibly rewarding experience that revitalizes your career in medicine - so don’t turn away just because of fear.

My hope is that this article gives you more information to boost your confidence.

Let’s begin.

WHAT ARE THEY ASKING OF YOU?

It’s important to know what you are signing up for. As physicians, it is essential that you know whether you will be acting or providing advice that uses your medical license.

If you need to be a doctor to make the decisions that you’re making in the company, this likely falls under your medical license. If something goes wrong, you are covered by the CMPA for any legal issues.

In comparison, if you’re acting in a role that does not expressly require medical knowledge - for example a non-clinical advisor - you are not covered legally by CMPA for any disputes that go down later (knock on wood). You can get alternative legal insurance instead.

Personally, I prefer doing non-clinical contracts, because I want to keep my medical license separate from the innovation work that I do.

Becoming Medical Director of a startup is most likely going to involve your medical license. Even if you’re not doing direct patient care, looking over healthcare policies and procedures requires you to wear your MD hat to make the best decisions.

In contrast, being a strategic advisor (what I do), does not usually require you to have a medical hat on, when you are careful not to give medical advice. I tell startups that I will comment on problem identification, product design, and help access channels into the clinical space, but I do not comment on whether something is safe, what they should do in particular patient scenarios, or anything remotely related to clinical policies and procedures.

Of course I’m still guided by my moral principles - if a startup is clearly unsafe, I won’t introduce them to anyone else and I will likely stop working with them if they aren’t able to fix the problem (with the fix being determined by their own team, not me).

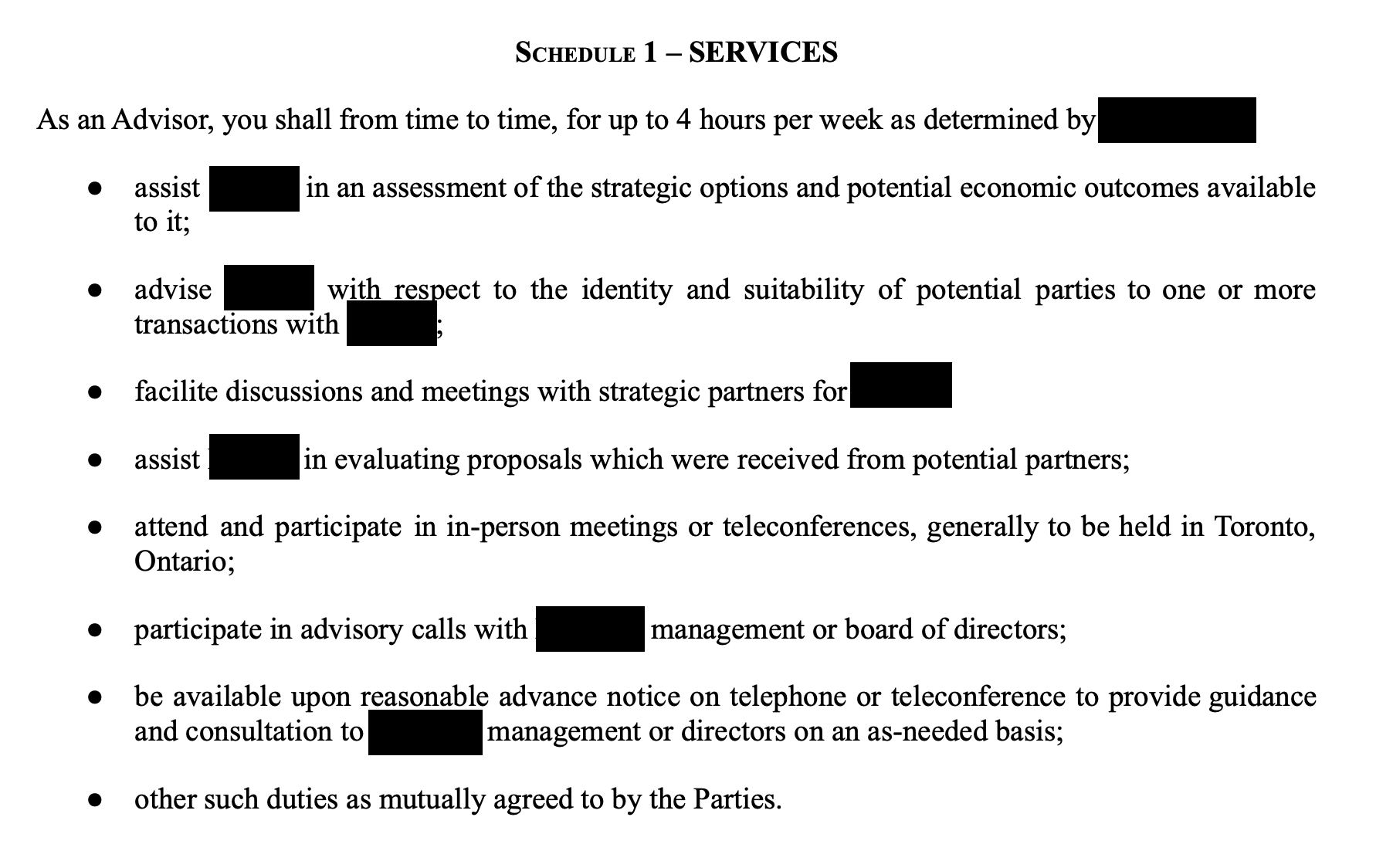

In this way, I’ve done my best to keep my medical hat separate from my innovation hat. Below is an example of the “services” in a contract of mine (the company is redacted for confidentiality).

WHAT ARE THEY GIVING YOU?

This is the fee structure that you’ll receive in return for your time.

There are two main ways that you can get paid by a startup - salary and equity - and you may end up with a mix of the two.

This of course doesn’t consider all the non-monetary benefits of working with a startup - like being part of something big and new, finding a renewed passion for healthcare, meeting interesting people, travel, and much more.

1) Salary:

You’re getting paid in cash every month. If you are a private contractor (it will say in your contract), and make more than 30 thousand (in Ontario) you’ll need to get an HST number and charge the company HST for your services on top of the agreed upon salary. Check with your accountant if there’s anything else you need to know based on where you live.

2) Equity:

You’re getting paid in stock options. If the company ever goes public, you can trade in these stock options for the price listed in your contract (e.g. $0.0528 in the case of my first contract) called the “exercise price”, and then turn around and sell the stocks for the now-market value (much higher than this exercise price), thus making a good return-on-investment.

With equity, there are two added layers of complexity.

A) What are they worth now? You’ll want to first calculate what the value of your stocks are right now, to figure out if you’re being paid fairly for your time. This requires you to know the current market value of the company, how many shares you’re getting, what price you would one day pay for them (the “exercise price”), over what time frame you’re getting them (the vesting schedule, which I explain below, and you might want to jump down to) and then doing some calculations to figure out your cut.

For example, they might say you’re getting 15,000 shares, or 0.1% of the company. This tells you that there are 15 million shares in existence (15,000 / 0.1%). Then, if the company is valued at 5 million, each share is worth $0.33 (5 million / 15 million).

If your contract says you can buy a share (when the company eventually goes public) for 0.0528, then the value of each share paid is 0.33 - 0.0528, or $0.27.

Now, multiply this by your number of shares to figure out how much you’re getting paid. In this case, 0.27 x 15,000 shares over 24 months = $4000 over 2 years, or $173/month.

I used some easy numbers here to make some of the math more simple. In reality, I negotiated my first contract for 0.3% of the company over 12 month vesting period with an exercise price of 0.0528 and a current market valuation of 8 million. This worked out to about $1800 in equity/month in addition to my salary. This was for 4 hours of work a week. I was able to negotiate this deal based on the OHIP fees for the income lost during that 4 hours of work as a geriatrician.

B) What is the vesting schedule? To avoid people signing on for one month and then cutting and running with a boat load of equity, the startup will set you on a “vesting schedule”, that dictates over what time frame you get your shares.

For example, you might be promised 0.3% of the company, with a 12 month vesting schedule, meaning that it will take you a year to get all of your equity and be “fully vested”.

C) What is the cliff? Again, to avoid people staying one month and getting a cut of the company, before the company has really obtained any value in return from you, they will stipulate a date in the future when you’ll officially get your equity.

Typically the cliff is set at 6 months or 1 year, with a monthly vesting thereafter. For example, if you have 0.3% of the company with a 12 month vesting and 6 month cliff, you’ll need to stay with the company for 6 months, at which point you’ll get 50% of the shares, and every month after you’ll get 1/12th.

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

Any new venture comes with risk. This could be risk in terms of lost income/time if the startup fails and your equity is never realized, or other non-monetary risks.

You’ve got to decide for yourself where your risk tolerance lies, and whether working with this startup makes sense for you.

There are a few things to keep in mind.

1) Think about the probabilities in addition to possibilities.

A common mistake I see is people jumping ship because of a potential risky outcome. That’s completely fine if you’ve logically analyzed the situation and found that the risk:benefit doesn’t work for you. However, make sure you have all the information, including knowing the chances of that bad outcome coming true, not just that it exists.

The easiest way to describe this to look at the NHS table for risk in digital healthcare startups.

Source: National Health Services, UK

It shows you how there are different categories of risk for digital devices, just as there are different classes of risk for medical devices. Turns out, you can apply this table to anything in life.

The key is to remove the level 5 risks - the things that are intolerable. I count losing my medical license and going to jail as level 5 things. After that, there are level 4 risks, that you want to mitigate by taking steps to reduce their chances of happening.

These steps could include things like making sure your contract is solid and you have indemnification, that you can leave anytime if you spot red flags in the company, and that you involve more people - consider getting a lawyer, legal insurance, and talking to people to get a sense of your colleagues reactions.

Ultimately, the majority of these kinds of contracts go well. There is no reward without risk. Take the leap, having put on water wings.

It’s up to you what risk you assume and what risks you avoid, but make sure you realize that even level 5 risks (dying and going to jail) can happen with or without working in a startup.

2) Make sure you have indemnification

This essentially means you can’t be found liable for something that the company does, that has nothing to do with your area of responsibility within the company.

Usually companies will also want indemnification from you - if you mess up, it’s not on them. This results in what’s called “cross-indemnification”.

My indemnity clause went like this: (NOTE THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE - MAKE YOUR OWN DECISIONS)

“The parties covenant and agree to indemnify and hold each other harmless from any liability, loss, damage or expense, including assessable legal fees, arising out of the negligent performance of their respective obligations under this Agreement or by anyone for whom they are in law responsible. The parties hereto agree that they shall cooperate with each other in the defence of any such action, including providing each other with prompt notice of any such action and the provision of all material documentation. The parties further agree that they have a right to retain their own counsel to conduct a full defence of any such action.”

3) Talk to People and Lawyers

If you know anyone in the industry, get them to look at the contract and point out any problems that they see.

Depending on how much you want to spend, you can also get a lawyer to look over your contract.

If you are going to be using your medical license in your role in the startup, it’s a good idea to get the CMPA to look over your contract before you sign anything. This is free - simply contact CMPA.

Be aware that they will tell you the worst-case scenario things that can happen. That’s their job. They also personally don’t want you to get sued (as it costs them money), and so it’s better for them if you don’t do anything remotely risky.

Use their advice to improve your contract, or decide not to sign if the CMPA has very strong concerns that upon reflection you realize are deal breakers.

4) Read things carefully and take time to think

Nothing is urgent in life, not even in the ICU.

Even in the ICU, there is time. The one caveat is probably Code Blues, but that doesn’t quite have the same ring to it.

If you feel like someone is rushing you, it’s a red flag. You can take your time.

If a deadline is missed, there is still always tomorrow. And if they really want to work with you, deadlines won’t matter. You can negotiate a deadline that actually works for you. Take your time and think clearly.

This doesn’t mean taking months, because startups move quickly (unlike other traditional business models / healthcare), but taking a few weeks or more is completely fine.

Bottom line: Don’t do anything rushed. Don’t do anything under pressure. Don’t let anyone make you think something is life or death. It never is. Except in a Code Blue.

5) Use Startup Tricks to Mitigate Risk

Startups are inherently risky, as I’ve said. However, startups have developed ways of reducing their risk, and we can use those same tactics when making deals.

For one, they make decisions on the small scale first - they build MVP’s, or minimum viable products, before committing massive resources to manufacturing a product that’s a dud. For you, this means having a few meetings with them over a few months before signing on seriously.

I tend to work with start-ups “pro bono” for 3-4 sessions. It’s kind of like early dating. If I like them, they seem stable, safe, competent, and trustworthy, then we might move to a contract stage. If I get any red flags, I trust my gut and politely end the relationship.

Secondly, you can lower risk by spreading it out. That’s how venture capital firms do it. They want to see that the company has already had some success - that other people are involved, there’s paying customers, that physicians are interested in the product, etc. Being the first people through a door is the riskiest period of time.

That being said, being first through a door is also the highest chance of return on investment. If you were an early employee at Amazon you’re now a multi-millionaire.

Lastly, remember that startups have a different mindset than people in medicine. A famous Silicon Valley saying is “move fast and break things”. In medicine, we tend to move slowly and have a visceral fear of breaking things. As we should. Patient’s lives are involved, and there are complicated moral and ethical aspects of care and innovation that need to be respected (something for a future article).

The point is, to work well with startups you’ll need to find a balance between these two extremes.

It’s actually a beautiful relationship, in my view. As healthcare workers, we can help the non-physician founders move closer to safety, and as entrepreneurs, they can help us understand that to change the world at scale, we have to take some risks.

If we want to build a new kind of healthcare, we’ll have to jump in together.

In Closing…

I hope this high-level overview of what to expect when negotiating contracts helps you make the best decisions for you.

Once again, I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice; everything you read today should be used at your own discretion and in concert with your own lawyers. If your lawyers say something different, go with that.

Happy negotiating!

Olivia

Dr. Geen is an internist and geriatrician in Canada, working in a tertiary hospital serving over one million people. She also holds a masters in Translational Health Sciences from the University of Oxford, is widely published in over 10 academic journals, and advises digital healthcare startups on problem-solution fit and implementation. For more info, see About.