The power of non-linear thinking

Subtitle: The simple mindset shift that will help you see things clearly

By Olivia Geen, MD, MSc, FRCPC

| 5 min read |

The world isn’t straightforward. It’s non-linear.

In his book, How Not to Be Wrong: the Power of Mathematical Thinking, Jordan Ellenberg explains linear and non-linear thinking.

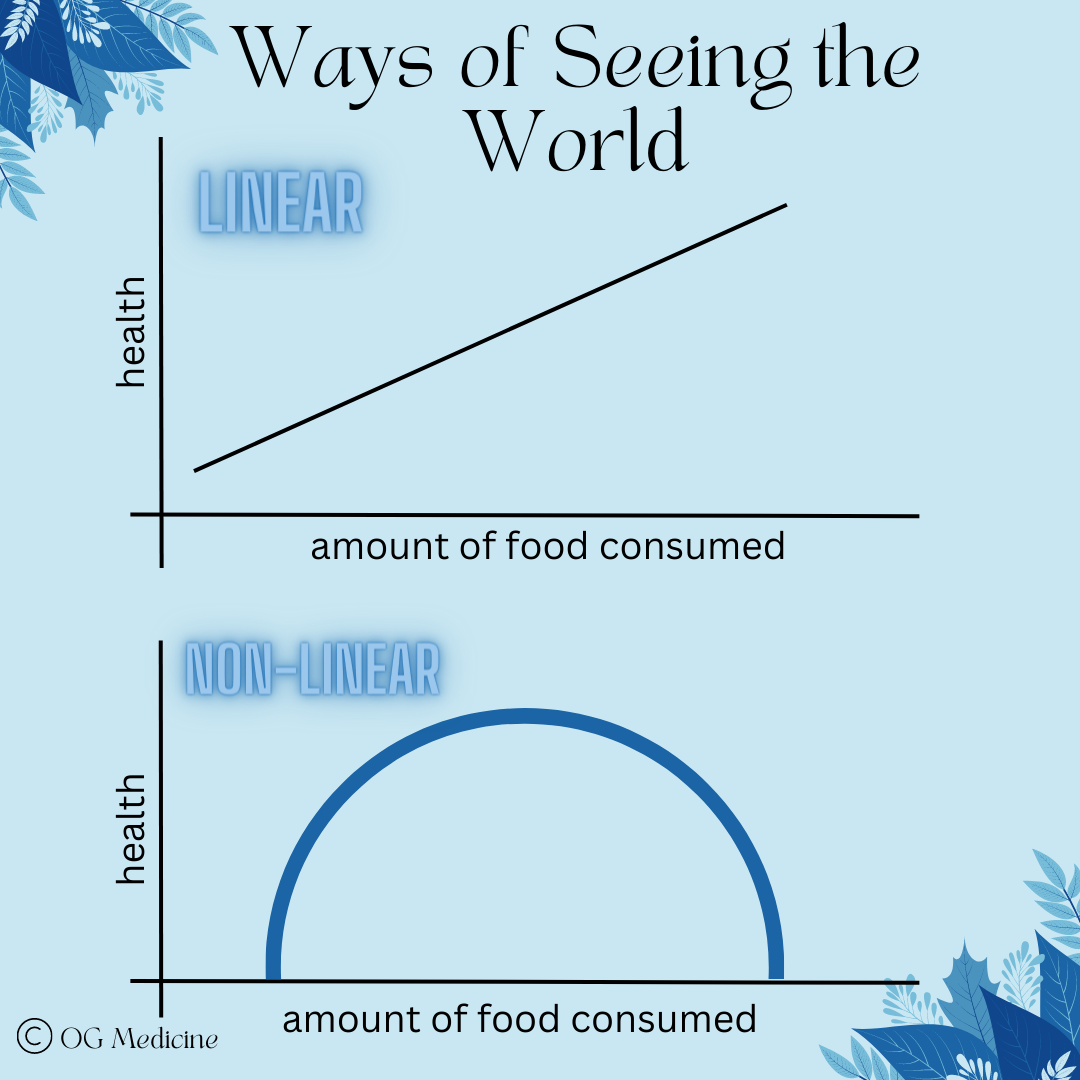

Linear thinking says - if a little of something is “bad”, then a lot of something must be “good”. For example, if not eating enough food causes you to starve, linear thinking would predict that eating more food will help you live longer.

We obviously know this isn’t entirely true… it’s possible to eat too much, which can be just as life threatening to your health (albeit over a longer period of time).

So if the relationship between food and health isn’t linear… what is it?

Obviously, it’s non-linear! With non-linear thinking, there’s a sweet spot of “somewhere in the middle” for almost everything.

Eating too much can be just as dangerous as not eating enough. Driving too fast or too slow can both be wrong. Spending too much money or refusing to spend any money at all are both foolish. The list goes on… the right answer for most things is in between.

In a world that likes to draw conclusions that are simple and straightforward, we can get the wrong answer when we forget that reality isn’t a linear relationship; it’s non-linear.

In some ways, non-linear thinking is the mathematical equivalent of equilibrium - life is a dynamic balance and the best answer is rarely in the extremes.

It also means that context is everything, because in order to know whether you should increase or decrease the amount of food you’re eating, you need to know on what side of the curve you’re already on.

“Nonlinear thinking means which way you should go depends on where you already are”

If you’re not eating enough food (left half of the curve), you need to eat more. But if you’re eating too much food (right half of the curve), you need to eat less.

How does non-linear thinking show up in medicine?

Remember that moment when you realized almost nothing in medicine is black and white? It happened for me sometime around the transition from medical school to residency.

I was working on the internal medicine CTU (clinical teaching unit) when it dawned on me that I was never going to get a straight answer from anyone. I had asked “so, if someone’s bleeding, and their hemoglobin is <70, we give them blood, right?”

My attending said something like “well… yes, but really it’s the trend. If they are at 90 and their hemoglobin was at 120 a few hours ago, you need to give them blood now, because the number lags behind what’s actually happening”.

“Okay…” I frowned. “So if their hemoglobin is <70 or if their hemoglobin is dropping quickly, I give them blood?”

“Well, yes, but also…” came the dreaded reply “you want to think about if they’ve got any blood thinners on board, what their goals of care are, and of course if they have a rare disease like sickle cell, then you want to be extra careful with blood transfusions because they develop antibodies and…”

In my memory this was the point where my eyes got misty and I stared off into space, wondering how I was ever going to know it all (narrator: she later learned it’s impossible to know it all; the goal is to know enough to surf the fundamental uncertainty of medicine).

The point, from this memory, is that the answer depended on what else was going on. It was never x + y = z. It was always contextual. What was going on before, after, and around the person.

Medical decision making is non-linear, the majority of the time. There might be some cases that are more straightforward (I knew an orthopaedic resident who would happily explain “If it’s broken, we fix it”), but 99% of the time, the right answer depends on the context of where you are on the curve.

How can we apply this to our work?

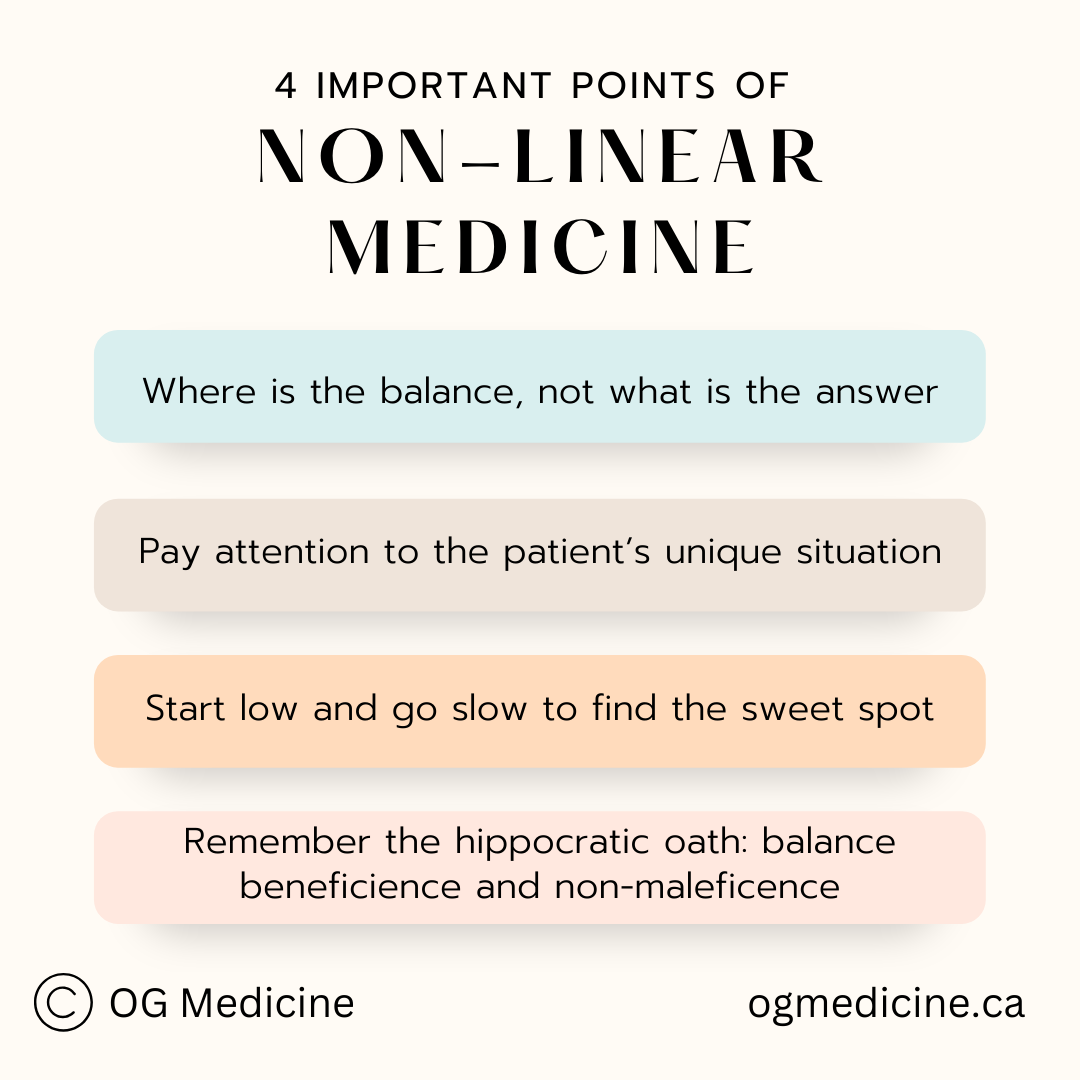

Now that we all see the light of non-linear thinking, let’s break it down into 4 take-home ways you can incorporate it into your daily decision-making.

1) Always ask yourself - where is the balance, not what is the right answer.

This means adapting guidelines to the situation. A 99 year old does not need to be on all of the heart failure medications recommended by guidelines; not only are they unlikely to live long enough to realize the time-to-benefit of the drugs, but they will also likely end up with low blood pressure, dizziness, fatigue, and falls. They are on the wrong side of the curve for benefit over risks.

2) Gather the before, after, and around - so that you can figure out where you are on the curve.

Context (or the unique patient situation) is everything. Spend time listening to the patient story, not just ticking off the boxes on a template in your electronic medical record. A “yes” or a “no” does not necessarily tell you where you are on the curve.

3) Think about balance when you’re prescribing medications.

Where is the optimal dose. Not the maximum or the minimum. For example, in patients living with dementia we often under-use pain medication, leaving people in unnecessary discomfort. Yet, at the same time, it’s well known that too much pain medication can make people more cognitively impaired (i.e. opioids are on the Beers list of ‘don’t use’ in older adults).

Luckily, you can overcome the indecision of not knowing what side of the curve you’re on by starting low and going slow. If you start a medication, simply make sure you book a follow-up to see what the effect is; this will tell you on what side of the curve you were (and are now) on. Did they get better? Great, keep going up on the dose slowly. Did they get worse? Yikes, dial back down. Keep tinkering until you reach the sweet spot for that individual patient.

4) Remember the hippocratic oath: find the balance between do-no-harm, and beneficence.

Our hippocratic oath actually lays out the concept of non-linear thinking. It tells us that it is our job not to fall into nihilistic thinking (what’s the point, nothing we do helps people anyways!), just as much as we mustn’t fall into the delusion that we are infallible (everything we do helps patients, they love medicine!). There is a balance between beneficence and non-maleficence that enables us to provide the right care for the unique person in front of us.

And there you have it - 4 ways to use non-linear thinking in medicine. What ways can you see non-linear thinking in your life outside the hospital? Comment below and subscribe to join the OG’ers club.

Happy loop non-linear thinking everyone!

Olivia

Dr. Geen is an internist and geriatrician in Canada, working in a tertiary hospital serving over one million people. She also holds a masters in Translational Health Sciences from the University of Oxford, is widely published in over 10 academic journals, and advises digital healthcare startups on problem-solution fit and implementation. For more info, see About.

Influences

1) Non-linear life events in medicine.

2) Jordan Ellenberg, How Not to Be Wrong: the Power of Mathematical Thinking, 2015.