So you want to be a doctor?

Subtitle: How to you know if you should go into medicine

Olivia Geen, MD, MSc, FRCPC

| 15 min read |

I’ve spent the last 7 years mentoring medical students, the last 4 mentoring internal medicine residents, and the last 2 mentoring subspecialty fellows (while working as a doctor myself in Canada).

I’ve heard it all - the angst over whether to go into medicine, followed by what specialty to choose, and then what subspecialty or fellowship to choose. There’s also questions around how to do well in interviews, how to pass exams, how to choose what hospital system you want to work in at the end. I’ve gone back and forth with learners on how to decide between community vs academic positions, how to choose a research project, and how to publish.

Through it all, there’s always been the thread of helping others find their path; what excites them, what brings them joy, and how to get there once you’ve decided on the direction.

Finding your path is one of the secrets to a happy life in healthcare, and therefore a topic I can’t wait to unpack for OG medicine.

With this in mind, I’ll be releasing a number of articles that gather up all those years of wisdom and mentoring into how-to articles with practical tips and direction for charting your course into, through, and after medical training.

I’ve been where you are. I’ve had those same questions. And I’m on the other side now, happy and loving life in healthcare.

Let’s start with the first question - how do you know if you should be a doctor?

STEP 1: Forget about “certainty” and go for “probably”

STEP 2: Gather information so you know (roughly) what to expect

STEP 3: Know how to listen to your head and heart (use logic and emotion)

STEP 1: Forget about “certainty” and go for “probably”

You don’t need to know from day 0 that you want to “be a doctor” in order to start the journey towards a career in the medical field. You just need to know that you want to take the next step.

The key is to gather enough information (which I’ll explain in Step 2 and 3), to dive in and trust that you made the best decision with the information that you had at the time.

You can never know for sure whether you should be a doctor before you actually get there.

So, instead of thinking in absolutes - that you need to know with 100% certainty if something is the “right” choice for you, think in probabilities; determine whether medicine is probably the best next step for you.

If that probability shifts, no stress, you can adjust from there (in another post I’ll go into transferrable skills and alternate career paths out of a MD degree; subscribe to find out).

So, how do you reach a good “probable” threshold? By finding out more information.

STEP 2: Gather information so you know (roughly) what to expect

To know if you want to be a doctor you have to get a better sense of what “being a doctor” actually means.

For myself, no one in my family had been a doctor before me - I come from a long line of pharmacists. So I shadowed a doctor here and there, spoke to my own GP, and read some books and articles on the topic (congrats, 1/3 complete by being here!).

However even with these experiences, the reality was that I still didn’t really know what it was like to be a doctor until I was one. Everything looked cool and exciting at first, because I didn’t see any of the boring/bad parts of the career. I only saw the good sides because it’s hard to show the bad in a one-day shadowing experience.

It’s like trying to explain to someone what it’s like to travel to Italy when they’ve never been there themselves. You can describe it to them, show them pictures, tell them how amazing the food was etc, but the other person won’t actually know what it felt like to be in that museum, or eating that food, or climbing that mountain, unless they’ve experienced it themselves.

This is why, as above, you’ll never be able to know with 100% certainty whether being a doctor is right for you. And that’s okay. Lingering doubt is fine. The goal is to get that doubt down to a manageable level by gathering enough information to feel comfortable with your decision.

It also helped to find out about other careers, and compare how I felt about those. I also looked into veterinary medicine, pharmacy, and research.

In the end, the little information I had was enough to make me feel comfortable pursuing medicine, as Step #3 will explain further.

Additionally, here are a few things I think are important to know about medicine so you have a better sense of what to expect:

#1: The job isn’t just about diagnosing and treating patients

Having an interest in physiology, anatomy, disease, diagnosis, treatment etc is necessary, but it’s only 1/10th of what the job is really about.

5/10th of the job is about interacting with people to solve their problems - patients, other healthcare workers, family members, etc

2/10th of the job is about navigating politics and bureaucracy from managers (or more, depending on where you work)

1/10th of the job is about feeling like a competent, respected expert

1/10th of the job is about feeling unappreciated and misunderstood

The exact ratios might differ between different specialities and at different times in your career, but in general, this is what post-training life as a doctor is like.

Some days you feel unstoppable because you just figured out a medical mystery, and other days you feel like all the years of work and sacrifice weren’t worth the stress and anguish.

No job is going to have 100% good days, so this isn’t a knock against medicine. It’s just me trying to show you pictures of Italy.

With this in mind, think less about what a doctor does and more about the skills you need to be one, and whether you like the sound of them. They include:

people skills - communication and collaboration to work with patients and colleagues

dedication & ability to sacrifice - you’re going to spend many years of your life studying and reading about medicine instead of doing other things in your 20’s.

creativity - the best diagnosticians use pattern recognition to make difficult diagnoses, which is a similar thought process to creativity

humility - the job is not as glamorous or even as respected as it used to be

curiosity - the job is life-long and the knowledge is ever-evolving; you’re going to continue learning and updating your skills for the rest of your career

emotional intelligence - you’re going to see a lot of trauma and sadness, and being able to process what you see is integral to the job.

#2: The day-to-day life is very different depending on what specialty you go into and where you work.

You can pretty much design any kind of life in healthcare if you’re willing to be proactive about figuring out what work-life balance you want when training is done, and choosing a specialty after medical school accordingly (I’ll show you how in future posts).

There’s no way around it - medical school and residency are rough. You won’t have much of a life.

But when it’s all said and done, if you pick a specialty and/or a place that has a large enough practice group (meaning enough other physicians in your field), you can likely pick how much you want to work to meet your financial and relaxation goals.

For some of you reading this, you might want to work 90% of the time in the hospital and 10% of the time be on vacation. For others, you might want to work 50% of the time in a clinic and 30% of the time in healthcare policy, and 20% of the time travelling the world. Or you might want to work 60% of the time hospital, 20% clinic, and 20% raising kids. Or 80% raising kids and 20% hospital. The point being, all kinds of variations exist but you’ve got to be strategic when the time comes. Again, future posts will get more into this, so subscribe if you want to learn more.

#3: If you go into a 5-year residency program, expect to not have much of a life outside medicine during those times.

Think about where you might be for those five years and ask yourself if it’s worth it. The lack of autonomy and control can be severe. We’re talking not being able to get a weekend off for your best friend’s wedding, or working 100+ hours a week, or delaying having children or scheduling your delivery around your exams. The list could go on, so suffice is to say - are you willing to give up your personal agency for 5+ years of your life?

You also won’t know where you’ll be living in a few years (as it depends where you get in for medical school, then where you match for residency, then where you match for fellowship, then where you can find the job that fits you…), which can give you sense of uncertainty about where you are in life which stalls other decisions like having kids, buying a house, etc.

Being able to say yes to this before you start will set your expectations and help to ensure that you aren’t struck with whiplash when residency begins and your personal freedom goes out the window.

That being said, there is a light at the end of the tunnel. If you follow the rest of the advice at OG medicine you can design a career post-residency that is exactly what you’ve always dreamed of.

STEP 3: Know how to listen to your head and heart (use logic and emotion)

Research has shown that when the connections to the amygdala are severed in the brain, people are unable to make decisions.

The amygdala is the power-house of emotions. Without emotions, everything loses relevance. The only way to know what is right, is to know what is right for you, and that requires both your emotions and your logic.

Being able to recognize your emotions is also a short-cut to “knowing yourself”.

You’ll often read the advice to “make sure you know yourself before picking a career”.

The trouble with this generic advice is that most of us are choosing whether to go into medicine at the age of 20 (although many of us find this path later in life) - we have to start early to build the grades, resumé, and study for the MCAT or USMLE.

At 20 years old you don’t really “know” who you are because it’s simply too soon - you’re still testing out all parts of life and figuring out your own unique views, likes, and dislikes.

So, rather than being able to articulate who you are, you just need to be able to articulate how you feel about a certain decision and combine it with what you think.

Step 3a: How do I know what I feel?

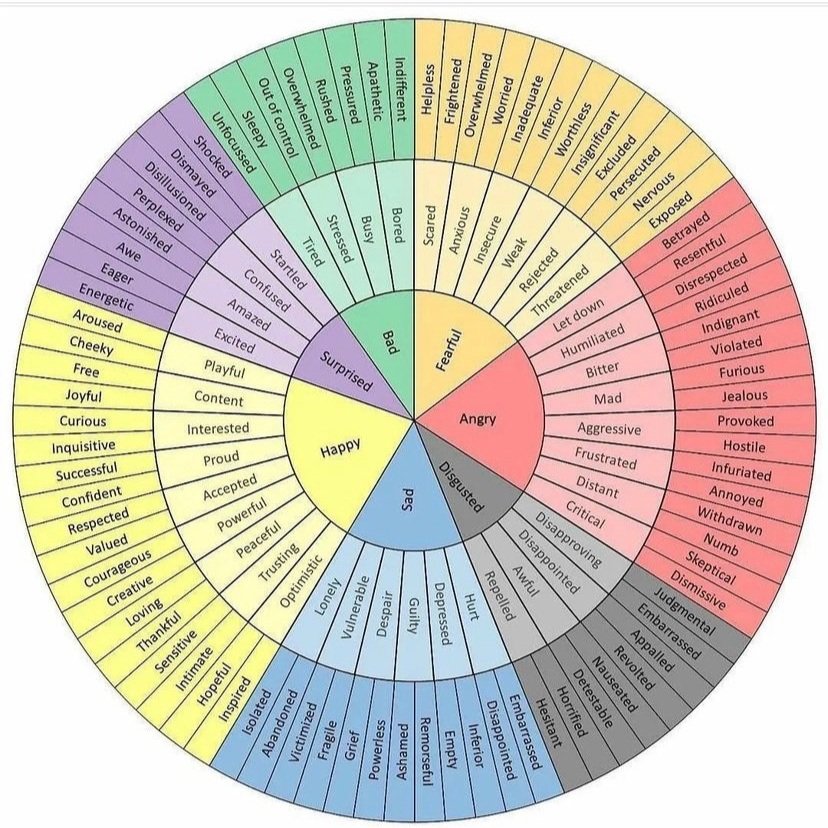

If you are not yet good at reading your own emotions, start to build up that muscle by using a simple tool like an emotion wheel (below) to ask yourself - how do I feel about “x” ?

You might also want to check out Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman, and take an EQ test to know what your strengths and weaknesses are.

Emotion wheel: honestly I’m not sure who created this, so I can’t give credit where it’s due.

When using the emotion wheel, the process can look something like this:

Ask yourself: “How do I feel about applying to medicine?”

Scan the center emotions and identify which ones (it can be more than one!) resonate with you - write them down.

Follow those emotions out to the periphery to pin-point exactly what you feel - write those down.

Put those emotions back into the context of what you’re dealing with.

Let’s work through two scenarios: someone for whom medicine is probably right, and someone for whom medicine is probably wrong.

Scenario A: Person A asks themselves, how do I feel about applying to medicine? Using the wheel, they find:

I feel happy and fearful, specifically:

Happy: interested (curious, inquisitive), optimistic (hopeful), and proud (confident)

Fearful: anxious (worried), insecure (inadequate) and weak (insignificant)

The context is:

I’m interested in going into medicine and hopeful that I can succeed in my dream, and proud that I want to do a career that is primarily about helping others,

AND I’m worried that I won’t get in, because there are so many smart people in the world, and I feel inadequate and insignificant next to other amazing applicants.

To this person, I would say - feel the fear and do it anyways. When most of the emotions that a question brings up are positive, except for fear, this is usually a green light to keep taking the next step towards your goal.

This is because fear is just a warning signal - something that can make you pause and consider if there’s a “safer” way to do something - it’s not the same as feeling repelled or vulnerable, in which case there might actually want to reconsider the decision and work out why those negative emotions are surfacing.

That brings us to Scenario B.

Scenario B: Person B asks the same question, how do I feel about applying to medicine? Using the wheel they find:

I feel sad, bad, surprised, fearful, and disgusted, specifically:

Sad: guilty (ashamed), depressed (empty)

Bad: stressed (overwhelmed)

Surprised: confused (disillusioned)

Fearful: anxious (worried), weak (worthless)

Disgusted: repelled (hesitant), awful (nauseated), disapproving (judgemental)

The context is:

I feel ashamed that deep down I don’t want to go to medical school, and I feel empty thinking about what else on earth I’m going to do. I’m stressed at the idea of not going, because I’ll be letting my family down. I’m confused that I feel this way, since I always thought one day I would want to go - it’s such a good career! Right?…. and now I’m worried I won’t find a better career and I’ll be worthless if I’m not a doctor. But when I think about entering medical school I feel hesitant and nauseated at the mere thought of it - why would anyone want to be a doctor?? Looking after sick people all day, postponing my life for 12 years with all the training… ugh. It’s just not for me. I want to build businesses, command board rooms… or something else, I don’t know… but I don’t know how to tell my family it’s not medicine.

You can see here how the two different people can ask themselves the same question - should I be a doctor? Both of them could probably come up with a very very similar list of pros/cons or logical arguments for why they should do it (it’s a respected career, you help people, learning about the human body is cool, etc etc).

Yet, when they check-in with how they feel about going to medical school - scenario A wants to go (and is just afraid to take the leap), while scenario B does not want to go but feels like they’ll be letting their family down.

In the case of Scenario B, being a doctor is unlikely what will bring them the most joy and satisfaction in life (although if they do go, there are ways to find your way back to those initial dreams of starting a business and running board rooms when those dreams inevitably resurface at age 25-50 years old… I’ll go into how to course-correct in a future post, but for now, relax in the knowledge that very little in life is truly unfixable).

But, my advice for person B would be to feel the discomfort of saying no, and say no anyways. Even though it’s hard - you’ve got to listen to what your heart is telling you. Otherwise you’ll be 50, feeling like you never lived your life the way you wanted, and instead lived your life the way other people expected.

That’s a recipe for a mid-life crisis, which as I said is not the end of the world - it’s never to late to course-correct! But, if you can start out on the course that feels best to you early, why not follow your head and heart to the dream career you’ve always wanted - medicine be damned.

Step 3b: How will I know I’m making the right choice?

You’ll know your decision is right for you when you hit the sweet spot of heart and head - it will feel like a “gut instinct” or intuition.

This will feel different from

a) just logic - which feels “spirally” and includes thoughts like “but what if…” and

b) just emotion - which can feel untethered, irrational, or like there are no thoughts behind your next move, just automatic reaction

When you’re truly tapped into both decision-centers of your brain - neocortex and limbic - you’ll feel a calm, low-key vibration where when you follow through the idea of what that decision would entail in the future, you feel a sense of peace and contentment with the decision.

For example, although I said it doesn’t sound like Scenario B would find their joy in medicine, they still have to combine those emotions with their logic.

Maybe not going into medicine would logically spell the end of their relationship with family (and they aren’t ready to push past family expectations), or they don’t logically have the years of experience they need to get into a top-tier MBA program.

It’s possible that their intuition will settle on something like - get the MD degree (3-4 years of medical school), but don’t go on into residency (i.e. never become an independently licensed physician). Use the M.D. to catapult into a career as a health-tech consultant, entrepreneur, or something else in business.

When Person B comes up with this plan, all the turmoil inside - the uneasy, uncomfortable, stressful sensation of uncertainty - settles down. There’s a calm feeling, and the incessant chatter of what do I do?? fades away. That’s how you know you’ve hit the answer that’s right for you.

You might still feel some lingering sadness or fear - any decision often comes with the loss of something (choosing one thing obviously means not choosing something else, and sometimes we might grieve for that loss) - but that doesn’t mean it’s not the right decision for you.

And remember - it’s never ever too late to course-correct. The decision you make today is a good one simply because it’s the best decision you could make with the information that you have right now.

If it’s the “wrong” call down the road, no problem. Future articles will delve into how to (re)design your life if you’re not on the path you truly want. There are ALWAYS more choices and decisions to be made that can change your life into the one you’ve always dreamed off.

Good luck - and remember, nothing is unfixable! Make a choice and see where it takes you.

Olivia

Dr. Geen is an internist and geriatrician in Canada, working in a tertiary hospital serving over one million people. She also holds a masters in Translational Health Sciences from the University of Oxford, is widely published in over 10 academic journals, and advises digital healthcare startups on problem-solution fit and implementation. For more info, see About.

Influences

1) My journey through pre-med, medical school, internal medicine residency, and geriatric medicine fellowship (12 years of post-secondary education).

2) My journey to a dream life in healthcare (MSc at Oxford, innovation and startups, writing, and direct patient care as a consultant physician in Canada).

3) Countless conversations with medical students, residents, and fellows as they charted their own course through healthcare - thank you!